The short story A Distant Episode agrees that civilisation might have bought us an objectively better life, but it explores what we might have unknowingly sacrificed to get these benefits, and asks whether having them torn from us might not be all bad.

A French Professor arrives in a poor village seeking to recapture a moment of friendship with Hassan Ramani, the owner of a local cafe, an event that happened during a three-day visit ten years ago. As he approaches the town he notes the smell of “orange blossoms, pepper, sun-baked excrement, burning olive oil, rotten fruit.” It’s the smell of a distant place and has an immediate effect on him as “he closed his eyes happily and lived for a moment in a purely olfactory world”. This is what he has come for, a return to something primitive and physical and beyond language.

He is a linguist, specialising in dialects and a successful man in his field. The driver who brings him is not impressed, telling him “There are no languages here, only dialects”, then adding cryptically, “Keep going south…you’ll find some languages you’ve never heard of before”. Words, for a linguist, are language, but there is a broader definition as “a system of communication used by a particular country or community”. Sometimes the reason we don’t hear of a language because there are no words to hear of in them. But soetimes the experience is all the more powerful because the words are missing.

A foreign experience

A stereotypical academic, the Professor’s knowledge is of books, not of people or the practical world, and he finds things going against his expectations right from the start.

His purpose for visiting is to catch up with the owner of a cafe he visited a long time ago, but when he gets there he finds the owner is deceased and the new owner is not happy to talk with him. He wants to buy a souvenir, a box made from camel udders. The new owner of the cafe is not happy about this, these are things, he says, that the “Ruguibat” (a tribe with an evil reputation) will sell and he offers to take the Professor to see them later that night.

As they walk through the town the Professor remarks that everyone knows the man. No one knows the Professor. He has spent his life studying the dialects of other people without being able to have a people of his own. This is why he has come to the village, to reconnect with someone he thought he could be genuine with. The Professor is seeking connection, and remarks to the guide “I wish everyone knew me”.

They go out through the back of town, passing through the “sweet black odour of rotten meat”, and then the smell of human excrement. He is instructed to pick up stones as there are wild dogs, and one with three legs comes running at them, only to be hit by a rock thrown by his guide. For a dog, movement (having all its legs) and biting (the dog has a broken jaw after being hit by a rock) are what makes it a dog. Without these things, it’s just a creature “scrambling haphazardly about like an injured insect”. And if that can happen to a dog, a native in the place, how much more likely is it to happen to a visitor from a distant place?

After a while, the guide feels he’s gone far enough and points the Professor down a path, asking for a tip and receiving 50 francs. He is left alone, in the moonlight, hearing the sound of flutes and becomes scared. He knows no one knows who or where he is and there is the feeling that anything could happen out here.

Leaving language behind

Left alone in the dark, the Professor thinks about what he knows of the place. He is alone and scared. He remembers words said in banter “When the Reguiba appears the righteous man turns away”. But these are just words, stories and he’s sure and safe in his knowledge of the world. Enjoying the scare of this episode in a distant place and thinking it will offer fuel for stories when he gets back to civilisation.

But if he is truly going to leave civilisation it’s not going to be easy.

At the bottom of the cliff, he is attacked by a dog, and a gun is pressed to his back. More dogs attack and he goes to the ground where the Reguiba start kicking him and take his money and everything in his pockets. He tries to call out to them to stop but “his bruised facial muscles would not work”. Like the dog who lost his leg, the Professor is starting to lose the thing that makes up his identity – language. The men continue kicking him until he is unconscious.

Embracing the physical

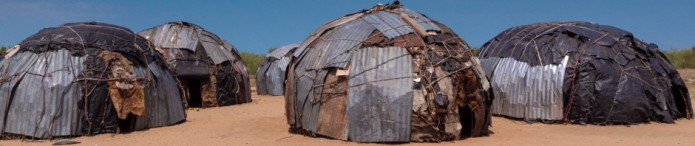

When he wakes in the morning, a man comes to him without speaking and cuts out his tongue. As he does so, the Professor accepts what is happening, “the word ‘operation’ kept going through his mind” and he becomes calm with the thought of it. He is put in a sack and carried away by camels to a village where the men “dressed” him up in tin cans tied together by rope. While they do this, the Professor “existed in the middle of the movements made by these other men”. With no tongue, the Professor is existing as a sort of passive consciousness, accepting what is happening almost as from outside his body. They arrived at another camp, and when he was healed “the Professor did not begin to think again, he ate and defecated and danced when he was bidden”.

The Professor begins to embrace the new world he has entered. The tin cans tied to him are no longer annoying, they make a racket, but it’s a “wonderful jangling racket”. The tribe take the Professor further southeast, “avoiding all stationary civilisation”, and when they pitch camp on a “wholly wild” plateau, “everyone was happy.” They teach him obscene gestures which “never failed to elicit delighted shrieks from the women”. You don’t visualise the Professor as the kind of man who would make women shriek in the civilised world he has been taken from.

But this is a distant “episode,”, so we know that whatever is happening to the Professor cannot last. This is not his place, no matter how much he has assimilated and accepted it.

The unredeeming power of language

They travel on, southeast, and plan to sell the Professor to another tribe. By now the Professor is well trained and has fallen into his captor’s “sense of ritual”. When they take him out there is no need to guard him as he doesn’t resist. He has reached a place where things can’t hurt him, but more interestingly a place where he has achieved some sort of happiness and acceptance. These people know him, he has a place and a role and an acceptance of life outside language, a place where language has been replaced by ritual and physical acts, almost like the urchins rising out of the dust when he first arrived.

But when they get to the place where he is to be sold the Professor understands the classical Arabic the new owner speaks and language starts to come back to him. “The pain had begun…because he had begun to enter into consciousness again”.

The result is he moves out of ritual and back into the world of language and memory. He refuses to dance for the new owner, who is furious with the men who sold him. The new owner kills one of the Reguiba, then is caught by the police. The Professor is locked up in the man’s house and when he doesn’t come back, he looks around and sees written words. This brings more memories and more pain. The reader is not sure whether it’s the pain of missing his own world or the pain of being torn out of the happy physical oblivion he has achieved.

Whatever it is, it makes him feel like “roaring” and he attacked the house and the door and goes into the street. He is free, but a freedom that sees him jangling and bellowing, beyond reason.

A distant eposide comes to an end

The Professor’s distant episode is over.

But even while language (and with it civilisation) is coming back to him, he does not try to stay in the town. He doesn’t do the civilised thing and go to the authorities – soldiers or the police – and ask for help. Instead, he leaves town as fast as he can.

He could be like a cowboy in a western, “riding off into the sunset”, only the Professor is no cowboy, or hero riding on horseback, instead, he is a fool running away, one who waved his arms “wildly, and hopped high into the air every few steps, in an access of terror”. This sunset isn’t a sunset of possibility like in a cowboy movie, it’s the end of hope, but it’s the only hope he has. The Professor has found his way out of language and into a temporary state of strange bliss. His rediscovery of language has brought him not sanity and civilisation, but terror.

As the episode ends, we see him fleeing the sunlight of reason and disappearing into the desert and its oncoming lunar chill that for all its privations offers him more than civilisation can.